Prescription drug abuse is a growing national epidemic. In a recent presentation, Dr. Leonard Paulozzi of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the number of unintentional overdose deaths per year involving opioid pain relievers (e.g., oxycodone and hydrocodone) nearly quadrupled from 1999 to 2007, rising from 2,900 to 11,500. Overdose deaths due to these opioids in 2007 were nearly twice that of cocaine-related deaths and more than five times that of heroin-related deaths. Data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network show that from 2004 to 2009 emergency department visits related to the misuse or abuse of oxycodone rose 242 percent, hydrocodone 124 percent and all pharmaceuticals 98 percent, while those for illicit drugs declined slightly.

Given these and other indicators, it’s no surprise that reducing the diversion and illicit use of prescription medications is a top priority of drug control and treatment agencies, including the Office of National Drug Control Policy, the Drug Enforcement Administration, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Bureau of Justice Assistance in the Department of Justice. Among the most promising resources recognized and supported by these agencies in this effort are prescription monitoring programs (PMPs).

PMPs are electronic databases, now operational in 34 states and planned in several others, which collect data from pharmacies on dispensed controlled substances such as opioid pain relievers, stimulants and tranquilizers. PMP data can help identify questionable patterns of prescribing often involved in drug diversion, such as a patient receiving multiple simultaneous prescriptions for opioids from different doctors filled at different pharmacies (“doctor shopping”). It’s important to note, however, that access to PMP data is tightly restricted in order to protect patient privacy, with heavy penalties for misuse.

Surveys have found that users of PMP databases, including medical providers and drug diversion investigators, judge PMP data as valuable additions to their toolkits. It’s often a PMP report that first alerts a doctor that a patient might have a problem with an addictive medication, triggering a clinical intervention if necessary. A recent analysis of Wyoming PMP data indicates that as prescribers received PMP reports on patients who were possible doctor shoppers, the rate of doctor shopping as measured by the PMP decreased, most likely because prescribers withheld medically unnecessary prescriptions from some of the patients concerned. A GAO report found that PMP data contributed to steep reductions in the time spent on drug diversion investigations, saving taxpayers money and keeping more drugs off the street.

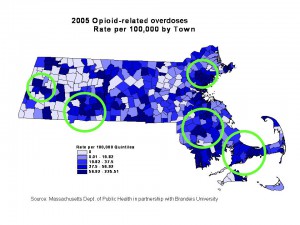

PMP data are now being used by drug treatment programs and drug courts to monitor purchases of controlled substances by their clients, helping to keep addiction patients safe from overdose and encouraging abstinence among drug offenders. They are also used by epidemiologists in tracking prescribing patterns (e.g., of OxyContin®) that might give early warning of a trend toward illicit use, and by medical examiners to help confirm a suspected drug overdose as a cause of death. Not least, because PMP data are the only direct indicators we have of doctor shopping rates, PMPs serve a crucial function in evaluating the impact of polices aimed at reducing prescription fraud, for instance, requiring pharmacy customers to show positive ID when picking up prescriptions.

Although PMPs are playing an important role in combating prescription drug abuse, they are significantly underutilized by health providers and investigators. They also need to be instituted in all U.S. states and territories lest those without them become centers of drug diversion. Existing PMPs need sufficient resources in order to be proactive in encouraging use of their data system and in sending alerts to prescribers and pharmacists who have possible doctor shoppers among their patients. A major enhancement on the verge of implementation is for states to share PMP data via a central information hub, permitting cross-state detection of prescription fraud and doctor shopping. State and national agencies, in partnership with private firms and universities, are also beginning to develop protocols to integrate PMP data with electronic medical records.

These improvements and initiatives will require ongoing institutional support at the state and national levels at a time when budgets everywhere are tight. But given the gravity of the prescription drug abuse epidemic, PMPs are a sound investment that will save lives and money. There are no alternative information sources that can serve the multiple functions of PMP systems, whether in drug control or public health, and PMPs have already proven themselves to be effective tools in curbing the diversion and misuse of controlled substances. In conjunction with other prevention, treatment and drug control strategies, they can help reverse one of the major public health epidemics of our time.

For further information on PMPs and their capabilities, please visit the websites of the PMP Center of Excellence at Brandeis University and the Alliance of States with Prescription Monitoring Programs. Both organizations receive support from the Harold Rogers Prescription Drugs Monitoring Program, administered by the Bureau of Justice Assistance, U.S. Department of Justice.

Tom Clark, Clearinghouse Manager,

PMP Center of Excellence at Brandeis University

Published

April 2011